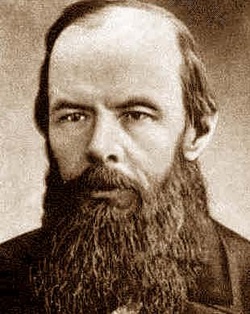

Dostoievskii

When Stephen Graham turned fifteen his father could not afford to keep him in education (there were by now five other young Grahams to clothe and feed). So Stephen became a Civil Service clerk in central London, commuting to the office every day from the family home in Essex. It was dull work. Stephen loved reading - at weekends he used to roam the country lanes reciting aloud from the poetry of Browning, or reading to himself the works of the nineteenth century philosopher Thomas Carlyle. And then, one day, Stephen found a second-hand copy of Dostoievskii's Crime and Punishment in a book barrow (see picture of Dostoievskii to the left). The grim tale of the murder of an elderly pawnbroker by the student Raskolnikov changed his life. Russia seemed a mysterious place and Dostoievskii's brooding novel hinted at things deep and mysterious. Many years later Stephen recalled how the book affected him. 'Let X be the soul of man, or let X be the ultimate meaning of life, something not familiar to the Western mind but, once sensed, forever haunting. I was on the trail of a religious philosophy more inspiring than Carlyle or Ibsen of Nietzsche'.

Stephen was not alone in falling in love with the idea of Russia. Although many Britons still viewed the country with deep suspicion at the start of the twentieth century - a place of violence and a threat to the British Empire - many more were tantalised by Russia's strangeness. There was a huge growth in interest in Russian literature and music in Britain from the 1880s onwards.

Stephen was not alone in falling in love with the idea of Russia. Although many Britons still viewed the country with deep suspicion at the start of the twentieth century - a place of violence and a threat to the British Empire - many more were tantalised by Russia's strangeness. There was a huge growth in interest in Russian literature and music in Britain from the 1880s onwards.